Mayor Mike Rawlings recently announced that the city’s annual Dallas Arts Week would become Dallas Arts Month, starting on April 1. Its centerpiece, the Dallas Art Fair, now in its ninth edition, has become a symbol of the local arts scene’s impressive growth and increasing momentum.

DALLAS, TEXAS — Here in Texas, things can be big — vast expanses of ranch land and sprawling cities born of oil and other big-industry money under very big Texas skies. To spend time in these iconic American cities is to notice the dynamism and diversity of their cultural communities and institutions, and how much more they deserve to be recognized on the national and international scenes.

With unabashed pride, the annual Dallas Art Fair opened here on Thursday. It will run through this Sunday, April 9, serving as a locus for the ever-stronger vibe of this city’s growing visual- and design-arts scene, and the institutions and resources that have developed to support it.

At a time when a reactionary federal government is targeting the National Endowment for the Arts, public broadcasting, and public education for destruction, Dallas’s civic leaders, unequivocally, all seem to get it — that a city’s vibrant cultural life is not only good for society but, in contributing to its overall quality of life, is good for business, too. Nowadays, any politician who fails to grasp that irrefutable, vital link between culture and the economy deserves to be given the boot (with a fine, handcrafted Texan snip-toe) into those dry, far-away pastures where only tumbleweed roams.

Mayor Mike Rawlings recently announced that the city’s annual Dallas Arts Week would become Dallas Arts Month, starting on April 1. Its centerpiece, the Dallas Art Fair, now in its ninth edition, has become a symbol of the local arts scene’s impressive growth and increasing momentum. At the fair itself, those trends are reflected in the greater visibility of galleries from other parts of the United States and overseas, as well as in its deepening relationships with local collectors and museums.

Money-where-their-mouth-is evidence of this kind of partnering was especially notable in a $100,000 purse provided by the Dallas Art Fair Foundation Acquisition Program to the Dallas Museum of Art. These funds, contributed by a pool of local collector-donors, enabled the museum to acquire works by the artists Justin Adian, Katherine Bradford, Derek Fordjour, Andrea Galvani, Summer Wheat and Matthew Wong from various exhibitors at this year’s fair.

The DMA’s new director, Augustín Arteaga, calls Dallas “an exciting city, with the largest arts district in the US.” Born and educated in Mexico City, Arteaga took over his new role here last September after several years as the director of the Museo Nacional de Arte (known as “MUNAL”) in Mexico’s capital.

Against the nation’s current political backdrop of racism, xenophobia, and disdain for culture, science, and the life of the mind, Arteaga’s appointment sends a strong signal that the region’s bicultural history and heritage have been enthusiastically embraced by the Dallas Museum of Art, which has firmly positioned itself as an international institution.

By coincidence, one of the museum’s current, large exhibitions, México 1900-1950: Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, José Clemente Orozco and the Avant-garde (on view through July 16), which had been on its schedule before Arteaga’s arrival, focuses on one of the richest art-historical periods of his native country. Presented completely bilingually, this broad survey recounts Mexican modern art’s development across genres in the first half of the 20th century, showcasing paintings, photographs and other works by leading figures of that time.

Back at the art fair, painting in its many forms is highly visible. Some galleries are showing smatterings of drawings, sculptural objects, photographs, or photo-based works. Mixed-media installations are few.

Dallas galleries tend to represent artists from Texas as well as other parts of the US. Among these exhibitors, Conduit Gallery’s booth features Houston-based Joe Mancuso’s spooky-elegant “Chandelier” (2014), a seven-foot-long, cone-shaped, wire-framed structure hanging from the ceiling and adorned with long-stemmed roses that have been dipped in concrete.

Conduit’s founder, Nancy Whitenack, who told me she appreciates fine craftsmanship, is also showing the collage and assemblage artist Lance Letscher’s newest works made from flattened and stapled-together pieces of antique metal toys. Conduit is also featuring small-scale, oil-on-gessoed-panel portraits by the British artist Sarah Ball, who in the past has produced unassuming but eloquent portraits based on police mugshots. With similar modesty, Ball has based her recent paintings on photographs of immigrants taken by Augustus Frederick Sherman, a registry clerk and amateur photographer who worked at Ellis Island from 1892 to 1925. He routinely asked his sitters to wear their home countries’ native garments.

Dallas’s Cris Worley Fine Arts is showing new paintings by Marc Dennis, who, in the past, working in a hyperrealist mode, conjured up cheeky send-ups of art history, such as a picture of two superheroes and a Russian mobster ogling the barmaid in Édouard Manet’s iconic “A Bar at the Folies-Bergère” (1882), or a version of Diego Velázquez’s “Las Meninas” (1656) featuring a disco ball. At the fair, Dennis’s new paintings fill canvases with explosions of luscious flowers, like classic still lifes on steroids. Worley is also exhibiting paintings by Paul Manes, an artist who recently left New York for Colorado and whose images regularly feature circular forms. Here, his big, oil-on-canvas “Jammed” (2017, 78 x 104 inches) depicts a pile-up of cut logs that serves, he has suggested, as a metaphor for today’s political stagnation.

Worley, who opened her gallery in 2010, said, “Local collectors who used to buy art whenever they went out of town are finding an ever-bigger selection and range of available work right here in Dallas. Plus, thanks to the Internet and the easy availability of information about art, people are better informed than ever before and more interested in art. These trends have helped the Arts District here develop.”

Dallas dealer Erin Cluley, who opened her eponymous gallery a few years ago after working at Dallas Contemporary, a non-collecting museum whose programming is local, regional and international in scope, said, “The Dallas Art Fair has fueled its own success by helping to educate people about art. This fair feels friendly and welcoming, and for many people here, it offers an opportunity to make discoveries. All of this has helped encourage buyers.” Cluley’s offerings include Dallas-based artist Nic Nicosia’s black-and-white photographs of scale-model set-ups of rooms filled with wire sculptures and other objects he makes himself. Meanwhile, at Cluley’s gallery space in West Dallas, the little props Nicosia uses in these staged photographs are now on view.

One of Dallas’s oldest venues for modern and contemporary art, Valley House Gallery & Sculpture Garden, is featuring new pictures by the African-American painter Sedrick Huckaby, whose commitment to portraiture reflects his abiding interest in the theme of families and communities as extended families, and by the Georgia-based artist Miles Cleveland Goodwin, whose portraits and images of nature or people in nature — farm fields, leafless trees in wintry settings, a little boy pulling his ailing dog along in a small cart — capture moments of heightened awareness of the world around us and, in reaction to it, of the stirrings of the soul.

Valley House co-director Cheryl Vogel recalled, “Miles Cleveland Goodwin seems quite reserved when you first meet him; he is a quiet man, but not aloof. One time he said, ‘I don’t talk much,’ and then, after I asked him a simple question about a painting, he went on to speak movingly, for two hours, about art, his ties to the land, and life. It was fascinating.”

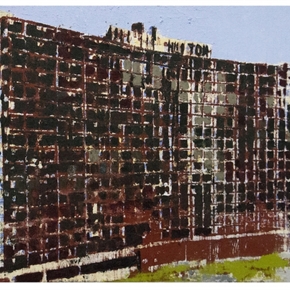

From New York, dealer Peter Blum is showing paintings by the Puerto Rico-born, Long Island City-based artist Enoc Perez, who has long been interested in architecture and employs a complex process of pressing a sheet of paper covered with oil paint against the surface of a canvas, and then drawing on the back of the sheet as it if were a piece of carbon paper. He has referred to this method as “printmaking.” It gives his finished images a haunting quality: modern hotels, Philip Johnson buildings, and Puerto Rican casitas become mysterious monuments, trapped in time.

Also from New York, Johannes Vogt is showing elegant abstractions — a wall-mounted, mixed-media sculpture and gentle watercolors on paper — by Garth Evans, the British sculptor who was once a teacher to such sculpture-makers as Richard Deacon, Antony Gormley and Tony Cragg. Manhattan’s Jane Lombard Gallery is featuring the work of the Ghanian artist Serge Attukwei Clottey, who uses cut-up pieces of large plastic oil or gasoline containers and little bits of wire to craft tapestry-like wall hangings with rich textures and a sculptural presence. A red-plastic afro comb affixed to a yellow tile on one of these large works serves as a reminder that Clottey’s found, repurposed raw materials once had practical value in someone’s daily life. Also from New York, De Buck Gallery is showing splattery, acrylic-and-broken-glass-on-canvas abstractions by Shozo Shimaoto (1928-1913), a member of Japan’s post-World War II, avant-garde Gutai group.

Numerous dealers from the United Kingdom, Ireland, Italy, Spain, Japan and other countries are participating in this year’s fair. Newcomer Eduardo Secci, from Florence, Italy, is showing conceptual artist Andrea Galvani’s photograph of an aircraft breaking the sound barrier (which the Dallas Museum of Art just picked up thanks to the Dallas Art Fair Foundation Acquisition Program), as well as a kinetic wall piece by the Swiss artist Zimoun, in which small, motorized cardboard tiles flutter like a bird’s wings. “Zimoun loves for his mixed-media sculptures to make noise; he likes the texture of sound,” Secci explained as he showed me photos of some of the artist’s large installations, in which 240 motorized cardboard boxes wiggle in a warehouse-like space, or 329 motorized cotton balls attached to strings pop and fly around a round, white room.

From Dublin, Kerlin Gallery offers a selection of bold-stroke drawings on paper by the Welsh-born artist Merlin James, who now lives in Scotland. Their subjects: trees, buildings, a curious tower, and a printing press. Hales Gallery, which has branches in London and New York, is offering a rare view of mixed-media drawings by Jeff Keen (1923-2012), a British maker of fast-paced underground films of juxtaposed imagery — today they would be considered visual mash-ups — who came from Brighton and whose art voraciously gobbled up its source material — found film footage, comic books, and more.

From San Francisco, Gallery Wendi Norris, long a champion of Leonora Carrington’s work (as well as that of other, less-familiar Surrealists), has on display some unusual, small Carrington works on paper alongside the geometric color weaves (paintings in acrylic on paper or canvas) of the veteran American abstractionist Peter Young. At Miami’s Cernuda Arte, one of the leading outposts in the US for Latin-American modern art, a fine selection of Cuban modernists’ works is on view, including Manuel Mendive’s oil washes on canvas depicting wispy spirits from a primordial dreamland.

From Los Angeles, Richard Heller Gallery is showing some of the humblest but most memorable selections of the whole fair — the Swedish artist Joakim Ojanen’s cast-bronze sculptures of cute-quirky animals; human heads with long, ribbon-like ears; and little heads with caps or top hats. With their subversive charm, free of self-conscious irony, this is the kind of art a tired ironist-entertainer like Jeff Koons could not even imagine creating. That’s because, for all its offbeat aura, Ojanen’s work is filled with soul.

At the opening of this year’s fair, co-founder Chris Byrne told me, “In 2008, when John Sughrue and I co-founded the Dallas Art Fair, we considered ourselves to be the audience; our intention was to create an event which, in addition to exposing the city to galleries from other parts of the world, would build upon the strengths of the local community.”

In a conversation with one gallery director from overseas, I remarked, “There’s a lot of money in this town.”

“Yes, and I hope to find it,” the dealer quipped, adding, “You know, I’ve done a lot of fairs, and of course everyone wants to sell. This is a business, after all. But I came here because the infrastructure of relationships they have built up between museums, collectors, galleries and the public really is attractive.” Another dealer, from London, said, “This business is all about building relationships; the commerce flows from those relationships.”

For all the bluster these days about the “art of the deal,” when it comes to dealing in art, infusing the familiar art-fair model with a discernible human touch might just be this event’s most valuable contribution to the field. In true Texas fashion, that alone is something big.

The author was invited to present a film at the Dallas Art Fair, which helped cover his expenses to attend the event.

The Dallas Art Fair continues at FIG (Fashion Industry Gallery) (1807 Ross Avenue, downtown Dallas, Arts District) through April 9.